–James Jordan, The Musician’s Soul (p. 48)

Have you ever experienced goose bumps while attending a concert? Do you know why? Was it a particular chord or climactic point? Were you transported to an associated memory? Because of the brain’s limbic system, where we process emotions, the music we hear should always create a response, good or bad; however, the most intense responses are when we connect with the performers themselves, either through the lyrics (supported by research) or with the presentation of the tune itself (performer’s honesty).

Concerning research on instrumental verses vocal repertoire responses to music, a commonly asked question is whether songs (with words) create a stronger response than repertoire without lyrics. Before knowing my grandmother’s own responses to music as an Alzheimer’s patient, a master’s thesis allowed time to personally tackle this question. After surveying over 90 subjects on their emotional responses to three versions of Amazing Grace – one solo instrumental, one solo vocal, and one instrumental/vocal combination recording – conclusions yielded similar results conducted by others in the field of music. One may assume the combination recording created a larger emotional response, and it did; however, the runner up was as intriguing being an instrumental educator. Because the presence of lyrics activates more networks in the brain due to speech and language processing (semantics), a larger emotional response or output is the consequence when lyrics are presented, which is supported by research. The type of emotional response is dependent upon personal choice (preference), environment, and circumstances surrounding the individual, obviously, but why does the populous lean toward music with lyrics verses without in general? My theory is that we ultimately yearn to FEEL MORE DEEPLY, despite societal norms screaming at us to show less vulnerability.

Life at the end of this millennium and the beginning of the next does not cultivate openness of spirit and spontaneous human expression. Instead, it breeds closure, protection of self, non-responsibility for any action or deed, mechanistic communication via computers and the Internet, and the harried pace of living. Combine all of those factors, and the result may be difficulty penetrating, much less communicating. Closure is evidenced in persons who hear but do not listen; who do not know spontaneous reaction: who do not understand their emotional make-up because they avoid it.

–James Jordan, The Musician’s Soul (p. 49)

As a performer, have you ever felt goose bumps on stage? Have you ever cried mid-performance at the beauty of a piece you are singing or playing? Or, did you possibly cry because you felt so openly vulnerable due to the crowd? Were personal circumstances or reflecting on associated memories overwhelming you during a performance? Was it a particular chord progression? Do you know why there was a profound emotional response?

An emotional disconnect of and to the performer is significant in today’s world; therefore, in reference to building a living, viable connection between our audience and the performer, James Jordan uses Martin Buber’s writings concerning I and Thou to help us understand the gravitas of communicating meaningful music to create emotional responses in music:

Rather, Buber implores us to believe that the conductor, performer, or teacher is connected to each member of the community [musician to self, musician to audience, musician to accompanist, conductor/teacher to ensemble] in a direct, one-on-one, eyeball-to-eyeball, soul-to-soul unison. Both are equal. Both are always equal. Both have equal voices. Both have powerful voices. Each listens to the other in a dynamic that is constant. It is almost like there is a spiritual tether or umbilical cord between the conductor and each person in the ensemble. Nothing can stand in the way of the flow of life and music between the two. It is out of those intimate human connections that the community gains a compelling and human voice.

–James Jordan, The Musician’s Soul (p. 76)

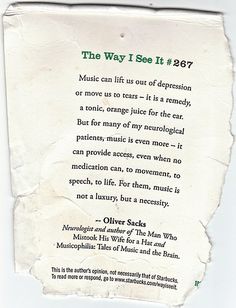

Have you discovered a desensitization after multiple performances of the same tune, or maybe felt that the music somehow healed you from the circumstances or memories yielding said emotions? From the earliest times in human civilization, music was referred to as ‘rational medicine,’ playing roles in healing, religious rites, and helping the emotionally disturbed. Later in the Medieval and Renaissance periods, it served as a remedy for ‘melancholy’ people - what we know to be depression today, and madness. It was prescribed as ‘preventative medicine’ to enhance emotional health. Imagine that! Of course, we also know today that listening to music releases endorphins - the chemical in the brain that tells us we are happy. Current research proves that performing music is also the only activity that activates both the left and right hemisphere of the brain, but not just that – it activates every region of the brain and nearly every subsystem.

However, therein lies the paradox - the penultimate untruth in the performing arts with music as a form of communication, and here is the secret: Music in not a universal language. If it were universal, each tune would take on the same meaning to every listener, which it most certainly does not. Music is not absolute (i.e. mathematics), but rather purely subjective. What could be universal (in a perfect world), is the way musicians, conductors, teachers, and students are trained and asked to communicate their music to an audience. Private instructors, music educators, and colleges of music must ask their students to individually dig deeper, beyond the black dots on the page and the aural skills training, and know themselves on a level that uproots the very vulnerability the composer or artist is asking within their works. How can we produce or re-create great art when we have no understanding of ourselves? Furthermore, how can a sense of honesty in the sound be communicated with the audience if “the sound is not alive and lacks the vibrancy that comes from many persons connected to both themselves and to the community at large?” (Jordan, p. 75) With that, how does one avoid desensitization as a performer?

Let us not focus all our efforts on building pedagogical technique, but rather allow more time discovering the pure knowledge of self. As humans, we have an innate desire to give to others, but in order to give musically in a way that honors the rehearsal and performance of artistic works, we must love ourselves and those with whom we are performing. We must be humble so our ensemble can thrive. “One cannot force oneself to love; but love presupposes understanding, and in order to understand, one must exert one’s self.” –Igor Stravinksy

My friends, the world is a noisy, active place, and despite efforts to reduce our accessibility and create alone time, it is nearly impossible to find today. Ask your students and fellow musicians to find their center through quietness, stillness, and solitude, and watch the selflessness and humility unfold as the ensemble finds the honesty, love, and peace needed to perform great art together as one, beautiful unit. Only then will your ensemble be able to effectively access the audience, creating profound and memorable emotional responses to music.

Rather than a soul in a body, become a body in a soul. Reach for your soul. Reach even farther. The impulse of creation and power authentic – the hourglass point between energy and matter: that is the seat of the soul. What does it mean to touch that place? –Gary Zukav, The Seat of the Soul (p. 248)

#music #musicians #musiceducation #musiceducators #performers #musicaesthetics #emotions

RSS Feed

RSS Feed