Dementia v. Alzheimer's

Dementia is a general, umbrella term for a decline in mental ability severe enough to interfere with daily life. Over a dozen types of dementia can produce impairments in memory, communication and language, attention span and focus, reasoning and judgment, and visual perception. Alzheimer's is the most common type of dementia (accounting for 60-80% of all dementia cases), and is a progressive, degenerative disease used to describe a specific set of symptoms. Other types of dementia are Dementia with Lewy Bodies, Vascular Dementia, Down Syndrome, Huntington’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease Dementia, Frontotemporal Dementia, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Posterior Cortical Atrophy, Traumatic Brain Injury, and several others.

Alzheimer’s breaks down further into Late onset or Early onset forms. The early (younger) onset form of Alzheimer’s is commonly caused by a familial genetic mutation passed down from a parent, with symptoms appearing in adults as early as their 30s, 40s, and 50s. Early onset accounts for roughly 5% of more than 5.4 million people living with Alzheimer’s in the US alone. Late onset, sporadic Alzheimer’s represents the other 95% of cases (approximately 5.2 million) with symptoms beginning at age 65 or older.

The Brain

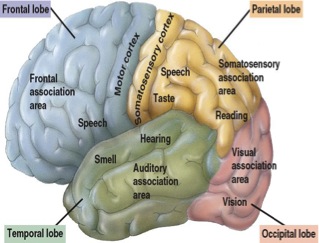

Before describing how Alzheimer’s spreads in the brain, it’s important to look at the parts and functions of the brain. Aside from the brain stem, cerebellum, and cerebrum, there is the outer, wrinkled surface called the cerebral cortex - a thin layer of gray matter covering both hemispheres. The cortex includes the frontal, temporal, occipital, and parietal lobes. Each lobe within the cortex is incredibly important and plays a key role in memory, attention, perceptual awareness, thought, language and consciousness.

- The Frontal lobe is involved in conscious thought and higher mental functions such as decision-making, particularly in the frontal lobe (prefrontal cortex), and plays an important part in processing short-term memories and retaining long-term memories (that are not task-based);

- The Parietal lobe integrates sensory information from the various senses, and in the manipulation of objects in determining spatial sense and navigation;

- The Temporal lobe is involved with smell and sound, the processing of semantics in speech and vision (faces and scenes), and is important to formation of long-term memory;

- The Occipital lobe is mainly involved in sight.

Many plausible and research-based theories exist on how Alzheimer’s ignites in the brain, be it by genetic mutation, hereditary factors, or even environmental triggers. The majority of research focuses on the vast spreading of plaques and tangles in the brain. Scientists have found that up to 20 years prior to symptoms being noticed, plaques (Beta Amyloid) and tangles (Tau) can begin to form in the brain where learning and memory, and thinking and planning originate inside the cortex.

Beta Amyloid is a sticky protein chemical that clumps together to form plaque. These clumps then block cell to cell signaling at the synapses, which we need in order to learn new information. This plaque can also become inflamed and destroy other healthy cells.

A transport system also exists for cells in nice track-like rows, where food molecules, cell parts, and other key materials travel. A good protein called Tau helps to keep these tracks straight. When tau collapses into twisted strands called tangles, they then fall apart and the transport system is destroyed. In tandem, plaques and tangles sweep through the cortex in a somewhat predictable pattern as Alzheimer’s progresses.

These plaques and tangles begin in the Lateral Entorhinal Cortex or LEC, the gateway to the hippocampus, which plays a key role in the consolidation of long-term memory among other functions. If the LEC is affected, then other aspects of the hippocampus will be affected. Over time, Alzheimer’s spreads from the LEC directly to other areas of the cerebral cortex, in particular the parietal cortex, where spatial orientation and navigation sit. Alzheimer’s spreads functionally by compromising neurons in the LEC, which then compromises the neurons of the adjoining areas. LEC dysfunction occurs when changes in tau and amyloid protein co-exist, and it is especially vulnerable in Alzheimer’s cases because the LEC normally accumulates tau, sensitizing it to the accumulation of amyloid – together these two damage neurons setting the stage for Alzheimer’s.

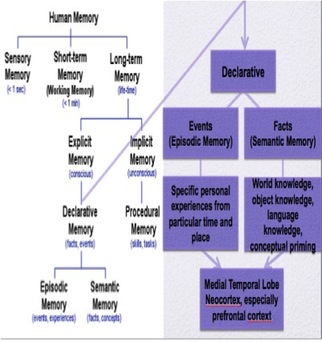

The Role of Memory

However, the amygdala may be our life preserver as chief officer of the limbic system, where we process emotions. In non-dementia patients, short-term memory functions are rooted through the prefrontal hippocampal networks, but since people with Alzheimer’s cannot process short-term memories there where the disease starts and spreads to all the other parts of the cerebral cortex, it may mean that the amygdala could help those with Alzheimer’s connect to short-term memories by presenting information in a highly emotional stimulus or context (music).

Symptoms & Current Research

Alzheimer’s symptoms can vary, but within the cognitive decline, manifestations in language deficits or failure in speech or naming are typically most noticeable first to the outsider. Verbal fluency, comprehension problems, deteriorations of spontaneous speech, indefinite words, repetition – these also all lead to isolation or what some call dialogic degeneration. And due to this, patients need interventions to address their needs and to prevent isolation. Regarding functional skills and as an extreme example, memory loss is not so simple as forgetting where one parked their car, but rather when one finds themselves forgetting the function of the brake and gas pedals in the car.

Beta Amyloid and Tau research is prevalent and includes the treatment trial currently in Phase 3 as reported in the news. We are still a long way from proving any medications can treat or relieve symptoms of Alzheimer’s in clinical trials over the coming years.

Another theory being researched encompasses the quandary of nerve cell deterioration as the pathology of an 80-year-old with symptomatic Alzheimer’s and one without symptoms can look physiologically exactly the same with plaques and tangles, so why does one person becomes afflicted with Alzheimer’s while another does not? Top neurologists believe the genetic biomarkers of our DNA, including stem fluids, carry proof that nerve cells are the culprit.

As of now, there is still no treatment for Alzheimer’s, no prevention, and no slowing down the progression of the disease. Memantine (Namenda) and Donepezil (Aricept) are FDA approved drugs to help cope with memory and functioning symptoms, but it does not alter the course of this disease in any way. What I can personally attest to is the efforts of leading neurologists and researchers from St. Louis to Pittsburgh, Rochester to Phoenix, and London to Sydney working alongside the Alzheimer's Association, doing what it takes to rid the world of this terrible disease.

What can you do? Talk about it. Donate your time to learning more at www.alz.org and protect your family from the struggles associated with this disease personally and financially - both as a caregiver and one who may become afflicted, especially if someone in your family had or currently has this disease.

Please call 1.800.272.3900 for help any time. Volunteers are available to help point you to qualified geriatrician neurologists and provide the resources necessary to meet your family's needs.

#EndAlz #Memory #Alzheimers #dementia #alzheimersassociation #brainresearch #betaamyloid #tau

RSS Feed

RSS Feed